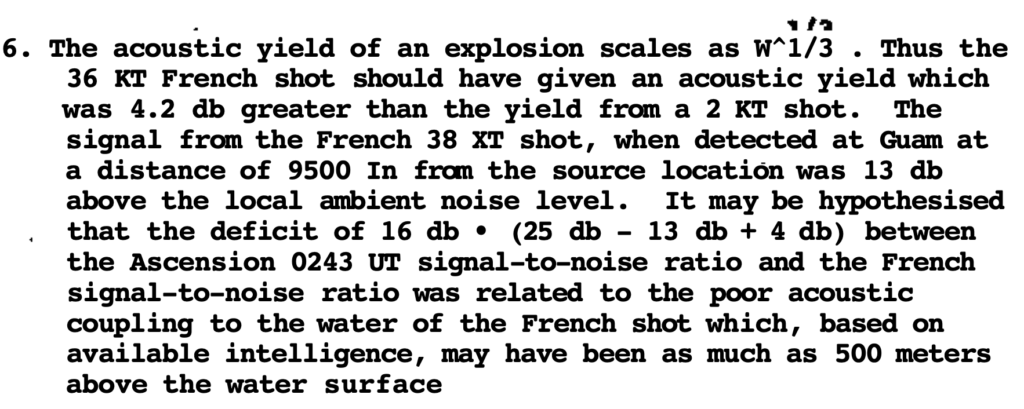

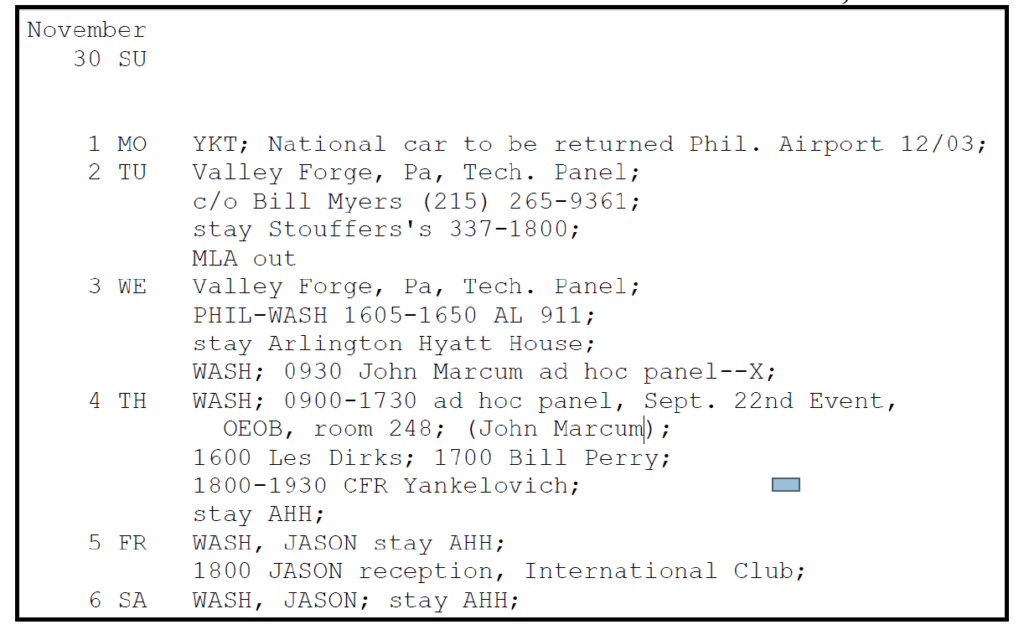

This1980 letter from US NRL Director Alan Berman has a data point about French nuclear tests in the Pacific of which I was unaware. Specifically, one of the tests’ yield was 38KT and was detonated “as much as 500 meters above the water surface.”

This1980 letter from US NRL Director Alan Berman has a data point about French nuclear tests in the Pacific of which I was unaware. Specifically, one of the tests’ yield was 38KT and was detonated “as much as 500 meters above the water surface.”

I wrote that “I am unaware of any case in which the OPCW or any other international organization has required a state to disclose stocks of an unscheduled chemical .” I was referring to the requirement in the July OPCW EC decision about which I wrote the other day. Syria must

(b) declare to the Secretariat all of the chemical weapons it currently possesses, including sarin, sarin precursors, and chlorine that is not intended for purposes not prohibited under the Convention, as well as chemical weapons production facilities and other related facilities;…

Based on what I wrote yesterday, I should have written that I was “unaware of any case it which the OPCW has required a state to disclose stocks of a specific unscheduled chemical.” Essentially, the CWC requires states to declare unschedule chemicals ” except where intended for purposes not prohibited under this Convention.” This is obviously similar to the July requirement, but doesn’t specify a chemical.

I posted a link on Twitter to this post and asked “Are there any cases in which the OPCW or any other international organization has required such an action?”

One reader pointed out that in May 2014 the OPCW confirmed “the destruction of the entire declared Syrian stockpile of Isopropanol” which, though a Sarin precursor, is not a scheduled chemical under the CWC. Now, I believe that the CWC required Syria to declare its isopropanol. The convention mandates that a party declare “whether it owns or possesses any chemical weapons, or whether there are any chemical weapons located in any place under its jurisdiction or control.” The convention’s definition of “chemical weapons” includes “Toxic chemicals and their precursors, except where intended for purposes not prohibited under this Convention, as long as the types and quantities are consistent with such purposes.”

It’s also worth noting that this September 2013 OPCW EC decision required Syria to submit “further information” about the “chemical name and military designator of each chemical in its chemical weapons stockpile, including precursors and toxins, and quantities thereof.” Syria had already submitted “detailed information, including names, types, and quantities of its chemical weapons agents, types of munitions, and location and form of storage, production, and research and development facilities…”

So there’s some precedent.

The July OPCW EC decision about which I posted yesterday contains what I think is an unprecedented provision. Recall the requirement that Syria

(b) declare to the Secretariat all of the chemical weapons it currently possesses, including sarin, sarin precursors, and chlorine that is not intended for purposes not prohibited under the Convention, as well as chemical weapons production facilities and other related facilities;…

I am unaware of any case in which the OPCW or any other international organization has required a state to disclose stocks of an unscheduled chemical .

*Update:* See this post.

Has there been much focus on this? The OPCW on July 9 gave Syria 90 days to comply with a number of steps. According to the text of its decision, the organization decided to “request, pursuant to paragraph 36 of Article VIII of the Convention, that the Syrian Arab Republic complete all of the following measures within 90 days of this decision in order to redress the situation:”

(a) declare to the Secretariat the facilities where the chemical weapons, including precursors, munitions, and devices, used in the 24, 25, and 30 March 2017 attacks were developed, produced, stockpiled, and operationally stored for delivery;

(b) declare to the Secretariat all of the chemical weapons it currently possesses, including sarin, sarin precursors, and chlorine that is not intended for purposes not prohibited under the Convention, as well as chemical weapons production facilities and other related facilities; and

(c) resolve all of the outstanding issues regarding its initial declaration of its chemical weapons stockpile and programme;

Here’s Article VIII, paragraph 36:

In its consideration of doubts or concerns regarding compliance and cases of non-compliance, including, inter alia, abuse of the rights provided for under this Convention, the Executive Council shall consult with the States Parties involved and, as appropriate, request the State Party to take measures to redress the situation within a specified time. To the extent that the Executive Council considers further action to be necessary, it shall take, inter alia, one or more of the following measures: (a) Inform all States Parties of the issue or matter; (b) Bring the issue or matter to the attention of the Conference; (c) Make recommendations to the Conference regarding measures to redress the situation and to ensure compliance. The Executive Council shall, in cases of particular gravity and urgency, bring the issue or matter, including relevant information and conclusions, directly to the attention of the United Nations General Assembly and the United Nations Security Council. It shall at the same time inform all States Parties of this step.

The OPCW decision also states that, should Syria fail to take these steps, the organization will

recommend to the Conference to adopt a decision at its next session which undertakes appropriate action, pursuant to paragraph 2 of Article XII of the Convention,

Here’s Article XII, paragraph 2:

In cases where a State Party has been requested by the Executive Council to take measures to redress a situation raising problems with regard to its compliance, and where the State Party fails to fulfil the request within the specified time, the Conference may, inter alia, upon the recommendation of the Executive Council, restrict or suspend the State Party’s rights and privileges under this Convention until it undertakes the necessary action to conform with its obligations under this Convention.

In this June 30 speech, UK Ambassador Jonathan Allen provided some details on Iran’s Qased SLV:

We are deeply concerned by Iran’s development of advanced technologies under the guise of Space Launch Vehicle research and the roles these technologies play in supporting Iran’s military ballistic missile program. We reject Iran’s claims that the Qased system used in their most recent launch is not a military launch system. In addition to the self-proclaimed role of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps in the launch, Iran’s official reports show a Transporter Erector Launcher, characteristic of military ballistic missiles and not a static launch done, or “gantry”, of the type normally associated with civilian Space Launch Vehicles.

The UNSG report to which he referred in his speech has more detail :

Iran stated that, unlike all of its previous space launch vehicle tests, this programme was developed and conducted by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps is a military entity known to control Iran’s strategic missile forces. The launch was conducted from an Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps facility in Shahrud which was not previously associated with such launches.

<snip>

The design of the Qased second stage is based on a new solid-propellant motor and incorporates a new attitude control module. This solid-propellant motor design is similar to the Salman system unveiled by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in February 2020 along with a range of other new ballistic missile technology, including the Raad-500 short-range ballistic missile. The Salman featured a flexible-nozzle control system, rather than jet vanes used on other Iranian solid-propellant motors. This technology improves the motor’s efficiency and is essential for the development of larger-diameter solid-propellant motors suitable, primarily, in the design of long- range ballistic missiles. Official Iranian media reporting in February 2020 showed a static test of the Salman motor at the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Shahrud facility. The test facilities at the Shahrud site include four additional static motor test platforms, which are only suitable for testing such larger-diameter solid-propellant ballistic missile motors.

Iranian state media reporting shows the Qased uses an attitude control module to control its orientation and flight path prior to satellite release. This technology has been derived from Iran’s development of ballistic missiles with manoeuvrable re-entry vehicles, such as the Emad variant of the Shahab-3 and the Qiam-2.

The attitude control system on the Qased demonstrated the capability to accurately control and orient a vehicle outside the atmosphere. This is an essential technology for the development of a long-range ballistic missile system capable of deploying both multiple re-entry vehicles and multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles.

I previously described this document as a “paper” written by Richard Garwin about the Ruina Panel. (Here, by the way, is a copy of the Ruina report, which looks as if it was faxed from Dr. Garwin’s office.). But the document is really a compilation of emails and notes from Garwin to the Wilson Center conference organizers. He devotes much space to discussing an NRL report about the Vela incident and related hydroacoustic evidence of a large explosion.

Here’ a 1980 letter from then-NRL Director Alan Berman concerning the report. Below is the Wilson Center Digital Archive’s summary of the document:

Alan Berman writes to US Office of Science and Technology Policy senior advisor John Marcum on hydroacoustic evidence on the Vela incident. Based on sounds recorded, it appeared that a large explosion occurred south of Ascension Island.

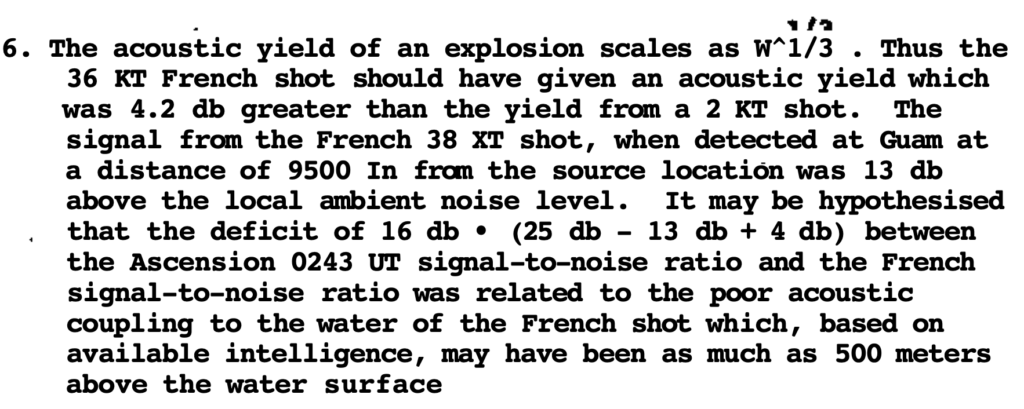

This material in the Garwin document seems to be Dr. Garwin’s travel itinerary for a December 1980 Ruina Panel event:

In this November 2019 paper, Richard Garwin discusses his time on the Ruina Panel, which investigated the 1979 Vela Incident.

I’ll write more about it later, but this line jumped out at me:

Only a subset of the Ruina Panel had extensive clearances for SCI– specifically,

technology and data from intelligence satellites.

I’m not sure I ever knew that.

About a month ago, the UN issued this document titled “Nuclear disarmament; follow-up to the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice on the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons; reducing nuclear danger.”

This past November, Leonard Weiss gave a short speech titled “My Involvement with the 1979 Vela Satellite (6911) Event.” He recounted this episode about a 1980 holiday party:

During the celebration, while [Senator John] Glenn and I were chatting, Gerard Smith, U.S. Representative for Nonproliferation Matters walked over to us with drink in hand to join our chat. Smith had met with both Glenn and me on prior occasions to talk about nuclear agreements with other countries, particularly Euratom, that were required by the Nuclear Nonproliferation Act of 1978…But now, at the party, Smith was more concerned with Glenn’s intent to introduce legislation to block an NRC decision to allow a shipment of uranium fuel for India’s Tarapur reactors under an old contract to proceed….When Smith told Glenn he thought letting the shipment go would be a good nonproliferation move, Glenn disagreed, saying that the Indians had been “bad guys” on nonproliferation issues. At this, Smith bristled and said “You think the Indians are bad gguys? If you want to talk about bad guys, talk about the Israelis!” And with that both men backed off and Smith took his leave. I was stunned by Smith’s comment and committed it to memory. I wasn’t sure exactly what Smith had in mind; the Israelis had vexed many State Department officials over the years with their deception on Dimona and their ostensible theft of HEU from the NUMEC corporation in Apollo Pennsylvania. But those events happened years before. There was now a new issue with the mysterious flash, and in retrospect I think Smith may have been telling Glenn that he believed those analysts in the intelligence community who thought Israel was the most likely perpetrator of a nuclear test detected by Vela 6911.