Category Archives: Uncategorized

Iranian Chemical Weapons in Libya

As readers probably know, the State Dept’s 2019 CWC compliance report states that Iran transferred “CW to Libya during the 1978-1987 Libya-Chad war.”

Here’s some more detail:

The United States assesses that in 1987 Iran transferred CW munitions to Libya during the 1978-1987 Libya-Chad war. Following the collapse of the Gaddafi regime, the Libyan Transitional National Council located sulfur mustard-filled 130mm artillery shells and aerial bombs, which are assessed to have originated from Iran in the late 1980s. In 2011, Libya declared to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) that it discovered 517 artillery shells and 8 aerial bombs comprising 1.3 Metric Tons of sulfur mustard but did not address the provenance of the items.

Well, the CIA was on this a while back. The 1988 report (which I cited here) mentions the transfer at least a couple of times. The report first observes that Iran’s CW production capability and stockpile were “sufficient to permit the shipment of chemical weapons to Libya in 1987.” It later mentions that “Iranian-produced chemical weapons have been transferred to Libya.”

CIA on Iran-Iraq CW Use and CWC

I have always been struck by the fact that the CWC entered into force less than a decade after the Iran-Iraq war ended. This 1988 CIA report seems pretty pessimistic about the convention:

It’s perfectly fair to describe the international response as “limited.” The document earlier notes the increased incentive for CW acquisition:

But such proliferation didn’t happen. Instead, no more countries used CW until Syria did. And most states are parties to the CWC.

Greece and Ottawa RevCon

I thought I’d bookend this post by nothing that, according to the final document from this past November’s Ottawa Convention RevCon,

There are now three States Parties for which the obligation to destroy stockpiled anti-personnel mines remains relevant – Greece, Sri Lanka and Ukraine – with two of these States Parties being noncompliant since 1 March 2008 (Greece) and 1 June 2010 (Ukraine).

…

Since the Third Review Conference, one of the main challenges in stockpile destruction has been the pending completion of stockpile destruction by Greece and Ukraine. Both of these States Parties have reported progress in destroying their stockpiled anti-personnel mines and have provided an expected end date for implementation.

USG Debate on Attacking Libya, 1988 Edition

This 1988 CIA document concerning options for a U.S. attack on Libya’s Rabta CW facility reminds me of a more recent debate concerning another country with a different sort of program.

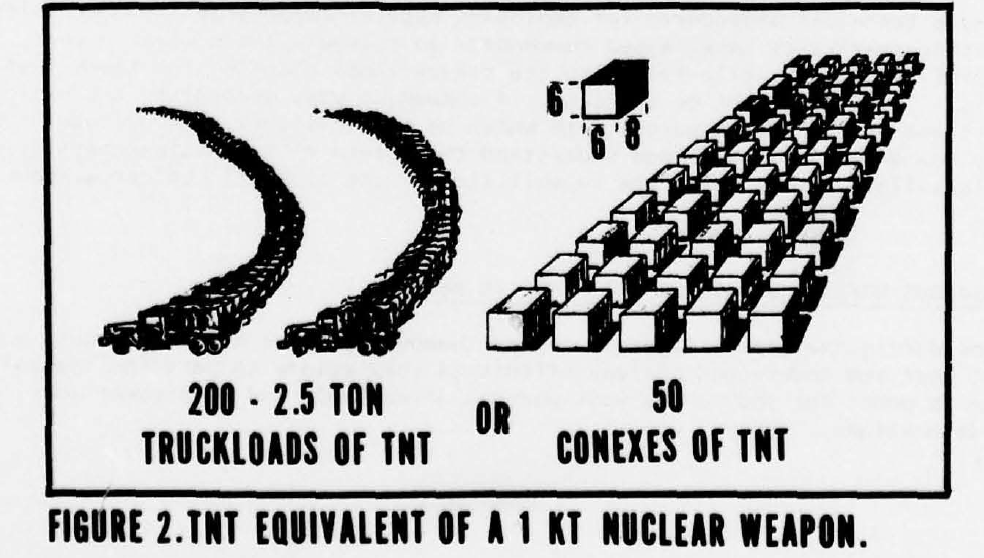

U.S. Army on TNT and Nuclear Weapon Yields

U.S. Army on TNWs

In 1977, the U. S. Army Nuclear Weapons Agency published The Primer on Nuclear Weapons Capabilities. The topic’s importance is self-explanatory to me, but the authors evidently wanted to keep the soldiers’ attention:

There’s a bunch of solid material in the primer, including this advice on minimizing the effects on TNWs:

CIA and India and Proliferation, 1974

In this post about IC reforms after mid-1974, I noted that I could not “think of a 1974 proliferation-related event which would have incentivized these changes.”

An astute reader pointed me to this July 1974 CIA study, titled An Examination of the Intelligence Community’s Performance Before the Indian Nuclear Test of May 1974, which fills in that gap.

CIA on Nuclear Proliferation, 1976

This 1976 CIA report titled Nuclear Proliferation and the Intelligence Community is worth your time. The report’s beginning describes some bureaucratic IC changes with respect to nuclear proliferation.

I cannot think of a 1974 proliferation-related event which would have incentivized these changes. The bulk of the document contains the recommendations of a report on proliferation intelligence prepared for the Deputy Secretary of Defense. The findings make for interesting reading, but I am not in a position to assess them. Also, if you really want an early reference to the IC and nuclear terrorism, here it is:

CIA on Iraqi Nuclear Weapons Procurement

This 1989 CIA report titled Iraq: Nuclear Weapons-Related Procurement Activities is an interesting read. I am struck by his assessment:

On an unrelated note, these two sentences seem to be in tension: