The history of the UK’s thermonuclear weapons program about which I blogged the other day repeatedly mentions a 1955 paper updating the 1950 version the 1957 edition of The Effects of Nuclear Weapons. Much of the discussion concerns potential UK H-Bomb tests.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

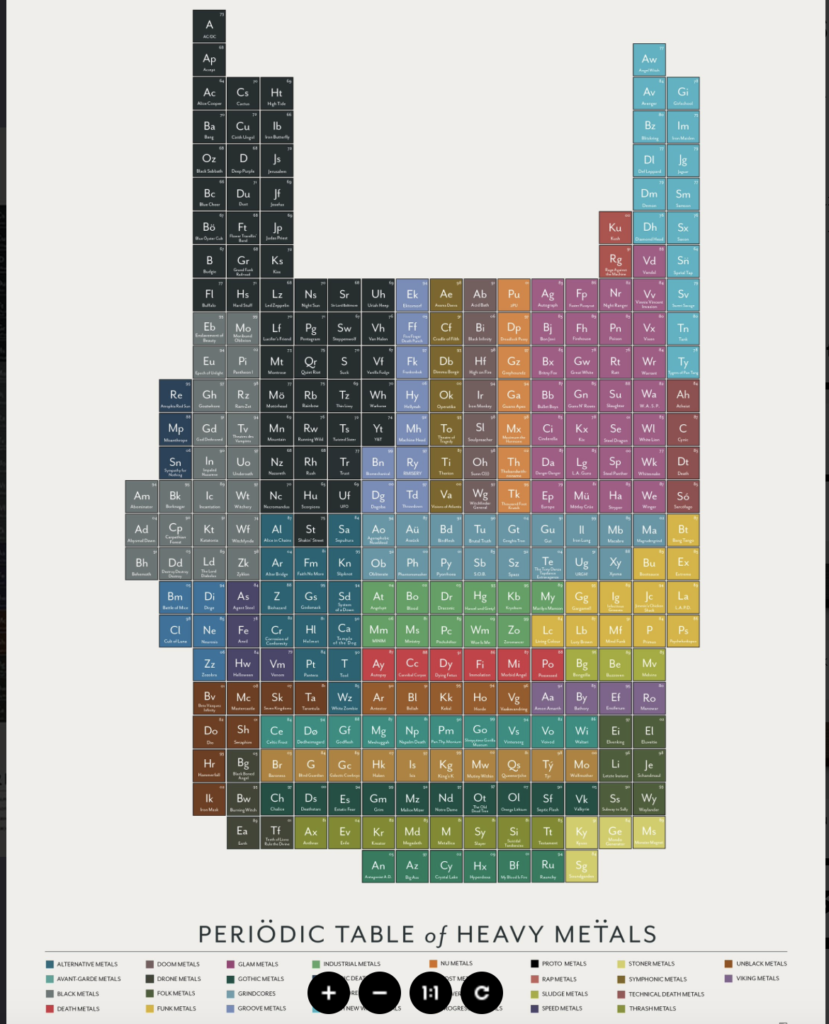

Periodic Table of Heavy Metals

I just received this as a gift.

Don Mahley on Libyan BW Program, 2004

The other day, I posted a excerpt from a November 2004 piece by the late Ambassador Donald Mahley. That excerpt discussed Libya’s CW program, but the article also has good material about Libya’s BW program:

Libya seems to have contemplated a biological weapons program. To support such contemplation, Libya decided to procure a dual capable facility, ostensibly for public health-related research, that would provide the option to pursue biological weapons research as decisions about such research were made. The Libyan scientific personnel charged with actually procuring the capability were not necessarily informed of the diverse purposes to which such a capability might be put – which is indicative of the broader international difficulty of pursuing biological weapons proliferators. All the elements of a biological weapons program, with the possible exception of specialized munitions and munitions filling equipment, also have peaceful uses. So it is entirely possible to conceal, even from your own personnel who might be working at a dual-use facility, the full range of purposes to which the facility might be put.

<snip>

The second success is more subtle. I indicated earlier that Libya had been unable to obtain the dual-purpose capabilities it sought in biology, potentially to become the foundation of a biological weapons program. Everyone should understand that the capabilities in question are not uniquely biological-weapons oriented. In fact, they were the kind of laboratory and research facilities that many countries have as part of their general medical capabilities to improve the health of national populations. The Libyan scientists pursuing this capability, in part possibly because they were not told about the potential diversion of capability, sought to contract laboratory construction with Western firms, where they had faith in quality control and delivery reliability. When they attempted to finalize the contract, however, the contacted firm declined once the location of construction was revealed, citing, according to Libyan officials, the problem of providing a country (Libya) under sanctions with the dual-capable equipment and facilities specified in the request. While this outcome illuminates the potentially draconian effect of sanctions when applied (the purpose of the construction could equally have been purely humanitarian), it is a rare revelation of how stringent sanctions programs must be in order to impinge on the kinds of covert and dual-purpose capability building rogue states can conduct.

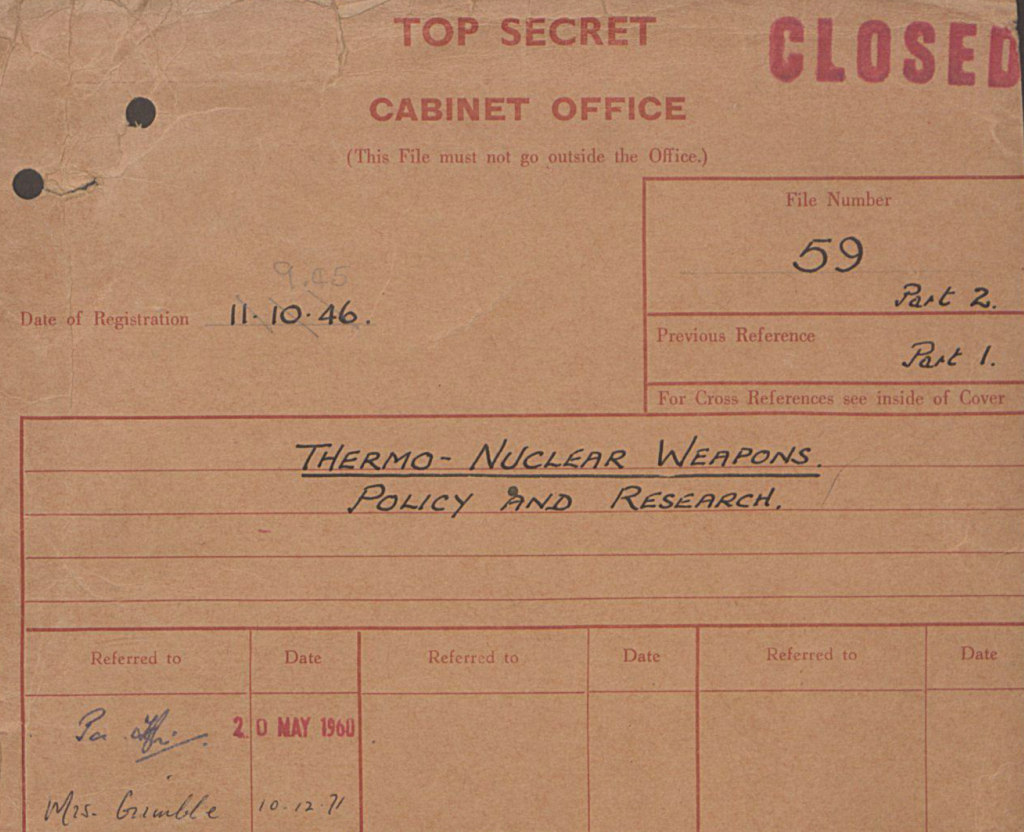

UK Thermo-nuclear Weapons: Policy and Research

The UK National Archive has a number of items available for free. I recommend a document set called Thermo-nuclear Weapons: Policy and Research. It’s too big for me to upload, so click here.

Arms Control Wonk on N Korea NW History

A little while ago, I wrote about a December 2019 article, written by Torrey Froscher and published by the CIA on North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Jeffrey sent me some insight about that piece and said that I could share it.

Some background: the article made this observation:

When North Korea’s nuclear program was in the formative stages, judging whether the intent was to develop nuclear weapons was a mystery, not a puzzle. Most of the analysis in the early years of the program, as described above, was agnostic about its purpose or noted both civil and military possibilities. This apparently changed by the end of 1991, when the program began to be characterized in definitive terms as a nuclear weapons program. The reason for the change is not made clear in the available record.

<snip>

In contrast to previous nuanced and cautious assessments of weapons intent, a December [1991] NIC memorandum judged that potential economic sanctions “would not cause North Korea to abandon its nuclear weapons program.”

Here’s the December 1991 memo. Here’s what Jeffrey said:

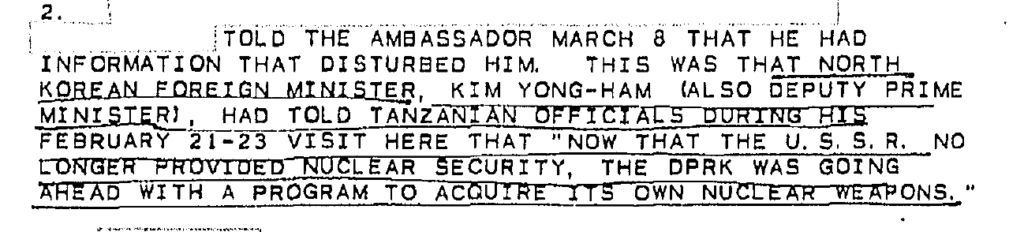

Well, I found a simple enough reason. In February 1991, Kim Yong-ham, at the time the DPRK foreign minister, told Tanzanian officials “Now that the U.S.S.R. no long provided security, the D.P.RK. was going ahead with a program to acquire its own nuclear weapons.”

Given the specific reasoning offered, I think something like this would be very hard to ignore.

I would guess this was not the only foreign government to whom North Korean officials made such comments. Froscher may be professing ignorance because the IC have gotten a more direct version, either through HUMINT or SIGINT, as opposed to a third party account like this.

Jeffrey was kind enough to send me a document. The whole thing is below, but I think this is the main paragraph:

William Burns Docs

Old news, but this site contains documents relevant to former Deputy Secretary of State William Burns’ 2019 book. And it’s searchable.

Don Mahley on Rabta, 2004

The late Ambassador Donald Mahley wrote a piece for ARENA back in November 2004. Titled “Dismantling Libyan Weapons: Lessons Learned,” it (unsurprisingly) has some good material on Libya’s Rabta CWPF and also on the broader Libyan disarmament case..

The whole thing is below.

Rabta also constitutes an interesting lesson from the Libyan experience…the lesson here is twofold. First, intelligence did not fail when it identified Rabta early on as a chemical weapons facility – despite the then vehement denials of the Libyan government and the doubt of numerous countries who wanted “smoking guns” to accept the intelligence assessment. Second, even when it was actively producing chemical weapons, Rabta was a “dual-use” facility. The chemical agent production lines were separated from the main part of the plant, behind separate walls. Fully dedicated facilities are not required.

With regard to the full extent of the program, an observation is in order. Prior to the December 19 [2003] announcement, there had been dialogue and even visits by select U.S.and UK officials. However, Libya obviously had not made a truly authoritative “full disclosure” decision until it was so announced in December. When we arrived in January [2004], we were voluntarily taken to additional resources that had not been discussed earlier. Our interlocutors were candid in advising us that they had not received instructions to be completely open earlier, so had only followed the instructions they had been given. The point here is not whether there was less-than complete disclosure earlier, but to point out that the incomplete disclosures were coherent and internally consistent, and involved all the major facilities that would have been required for a complete program. The additional materiel disclosed in January would have taken a lengthy dialogue and on-site set of procedures to uncover without Libyan cooperation. The lesson to learn? It is relatively easy, evenin a country where the bulk of the territory is open desert, to conceal elements of aWMD program if there is national dedication to do so. The idea that a single or even repeated short-time international inspection routine is sufficient to provide high confidence nothing has been missed is truly viewing the situation through rose-colored glasses. It is a tough job that requires considerable time and expertise.

B Pellaud on Israeli Nuclear Weapons

Old, I know, but former IAEA DDG for Safeguards Bruno Pellaud made these comments in a 2013 interview about Israel’s nuclear weapons:

Their own bomb provides them with a sort of immunity and in reality, for them, Iran is a danger not only because of the risk of a bomb, but because of its influence over neighbouring states – over Hezbollah, Syria and Lebanon. Israel is behaving in flagrant bad faith. When I was in Vienna, every three months I had a visit from their ambassador who told me: “The Iranians are three months away from having the bomb”. That went on for six years. And now Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu is continuing to exaggerate, but there is no value to it

State Dept on S Asia, April 2020

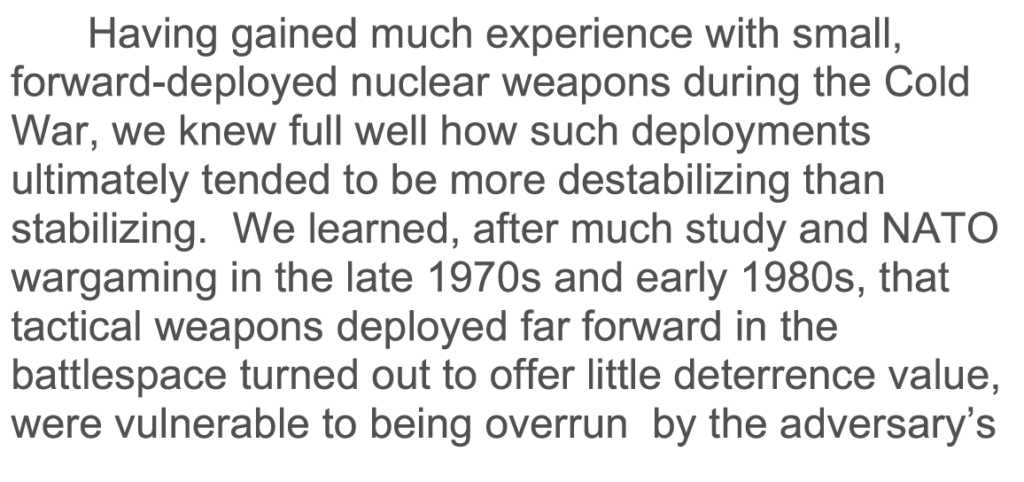

This report published by State last month briefly exhorts India and Pakistan to refrain from possessing tactical nuclear weapons.

President Sardar Masood Khan Interview

This interview with Azad Jammu and Kashmir President Sardar Masood Khan doesn’t really have anything about nuclear weapons. But it does mention a connection I hadn’t made…. President Khan was Pakistan’s Chief Negotiator for the Nuclear Security Summit, as well as Chair of the 2006 BWC RevCon.