From the same transcript I posted yesterday. This part is long, but worth a read. The whole transcript is great for details about intel community changes circa 2008.

I will start with this portion. I always thought that the personality-driven explanations behind the NIE were shallow:

The characterization of me as the author – I know exactly where it came from. I won’t share that with you tonight, but it got repeated and repeated and repeated. It was part of a very conscious – no need to deal with the substance of the product if you can have ad hominem attack that discredits the product.

In this portion, Fingar addresses the question of political pressure:

MS. DUFFY: There are a number of comments from attendees about the way that the Iraq WMD report might have been read or ignored or shaped by political agendas and so on. And there is another question: were there pressures from the White House or elsewhere in the government to suppress or modify the assessment of Iran’s nuclear weapons program, the most recent one?

DR. FINGAR: That I can say categorically, there was absolutely no pressure, interference from the White House or anywhere else in the administration. That’s not meant to try and inbound it. I’ve been at this quite a while. And one of the things that is sort of deeply ingrained in analysts is to have alarm bells go off and start acting like a wild man when they think somebody is improperly trying to exert political influence on his or her judgments. I have an ombudsman who is available and who – we tried to fireproof this estimate every way we could. I had my evaluations standards people go over it. I had the ombudsman sort of reach out. No is the short answer; the administration did not interfere in this.

The rest of this is about process and substance:

But as it became clear we needed to do this, we did it, and the lessons of Iraq – we went back to scrub everything. No prior judgment was allowed to stand unchallenged. No previously examined piece of evidence was taken automatically to have the same meaning as it has been given earlier. The context here of the war in Iraq, the context of the intensive politicization of that war. And even though I had learned long ago in Washington, there are only two possibilities. There are policy successes and intelligence failures. You have never heard anybody claim the opposite: The intelligence was brilliant and the policymaker screwed it up, and you probably never will.

That meant that what we produced on Iran’s nuclear program was going to be scrutinized by the congressional oversight committees that had scrutinized – it took them more than a year to do their post-mortem of analysis of the estimate that had been written in two weeks. They were ready to go to look at the next one that we did. Actually, the next one we did was on Korea – didn’t get that kind of scrutiny. There was a conviction in the minds of some that we were preparing to invade Iran. So get this estimate to us right away; we want to know if this is going to be another excuse for political action.

We worked harder on this, I think, than we, as a community, worked on any. I’m not the author of it. By the end of this, there were in excess of a hundred people who worked on this estimate. There were principal drafters. For reasons I hope were more or less obvious, we never reveal the names of individuals – they pay me big bucks to be the guy that takes the bayonet, but I didn’t write this thing. It was done by people who really know the subject.

I read what I thought was the final draft in June. We were finishing it up to deliver, as promised, during the summer. It was a pretty good estimate. Basically, it confirmed what we had said in 2005 and 2002. There was some detail. We answered some new questions, but basically it hadn’t changed anything. Right at that point, we got new information, incredible new information. So this guidance I mentioned earlier to – you know, what is it that you want, what is it you need, what will give you the – the collectors did a fantastic job.

And it wasn’t one source; it was multiple sources, and it was voluminous information. And we went all the way back to the beginning and said how do we look at this new stuff in light of what we already knew? How do we validate the new stuff against what we thought we knew? Where here are differences, which one do you come down on? Hundreds of names. Incredible technical detail in this. Bringing in specialists at the weapons labs to do this.

A couple of months into it, we realized that depending on how we came out on the reliability of the information, we could be changing a critical judgment, and we began to alert people that we had not made a decision yet. The jury is still out, but it might change an important judgment about Iran’s nuclear weapons program. Well, fast forward, we reached the conclusions that we did.

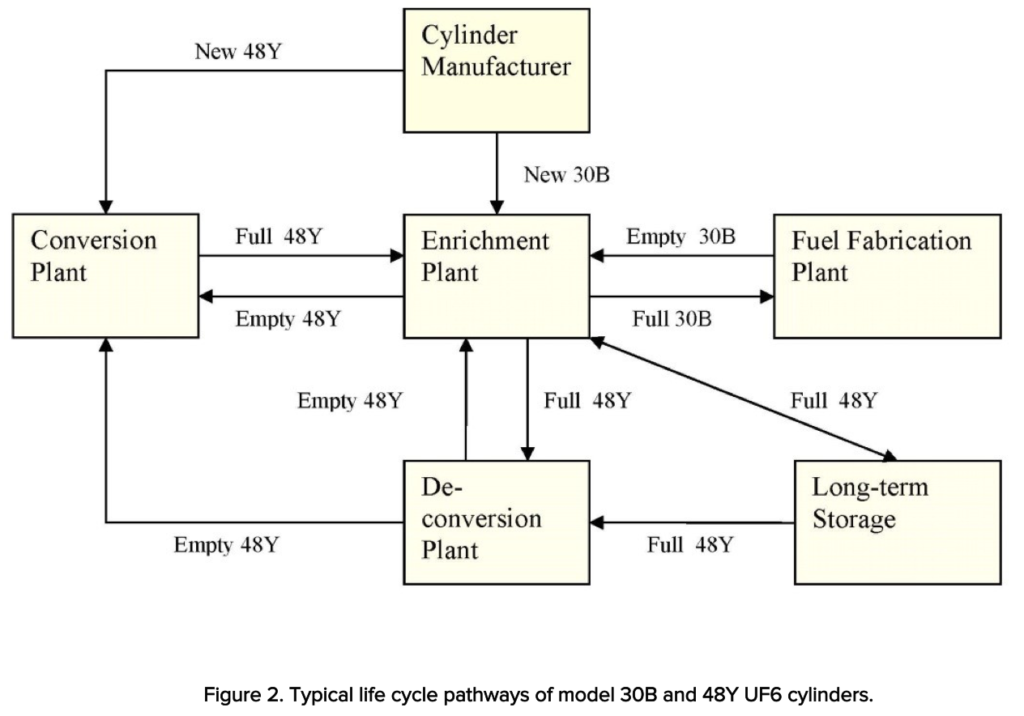

One of them was to nail with much greater certainty than we had before the existence and the scope of a secret weapons program that Iran has never admitted to, and continues to deny. We identified that Iran continued to press ahead with two of the three critical elements of it: production of fissile material – if you don’t have fissile material, you can’t have a nuclear weapon – in violation of U.N. Security Council resolutions, and continued to move ahead with a missile program to deliver a weapon.

What the estimate found was that in 2003, the Iranians halted the weaponization program and some other covert activities in response to international scrutiny and pressure. That’s the way we wrote it up in the summary of this. Also went through another – timelines, how long it would take them, and so forth, that really were corroboration of things that were – but what got attention, when this was released – and that’s another story here. We wrote this and said this should not be released. Sourcing is too sensitive, the arguments are too sophisticated. It was written for people who worked the issue, have the background.

The fact that we had changed a critical judgment posed an integrity dilemma. Since two directors of national intelligence in 2007 were on record with Iran is determined to have a nuclear weapon, and I was on record – I was the last one to have testified last summer on threat hearings on this – said, given the role of the American judgment in the international political debate, doesn’t integrity sort of require sort of telling the world we changed our mind on some thing? We changed our mind because we had new information. It wasn’t sort of a whim – that we had new information that led us to that conclusion, in a process that had looked at almost a dozen alternative ways of explaining what we had.

<snip>

MS. DUFFY: So Iran is a political decision away from nuclear weapons. Can you – obviously from an open-source perspective – can you talk about that a little bit more? What does that mean? And how long would it take them to implement such a political decision?

DR. FINGAR: The judgment in the estimate – and I’m not going beyond what’s sort of in the unclassified, if you actually read it and understand what you’re reading here – we didn’t change the timeline on how long they would have fissile material. We didn’t change our timeline on how long it would take them to have a device – a device is something like the North Koreans have; it will go bang underground; it will go bang someplace; harder to make it deliverable and to get it small. But though there is a lot that we do not know about how far along they were in this process.

Unfortunately, the technology to make simple nuclear weapons is now 70 years old and it’s pretty readily understood, widely available. The key is fissile material. And the hard part is the miniaturization for development. So it wouldn’t take long in our judgment.